The human species was born as stripped-down from standard features of homo heidelbergensis, not as supplemented. When ruthless nature in Africa exterminated the adult phenotype, it could not kill out the few members of the adolescent phenotype. They escaped extinction by using their willpower. Due to a natural whim (genetic defect), they had retained a teenage mind which allowed them to hide from the destructive effects of the environment. Their survival was undoubtedly also aided by another feature belonging to their teenage mind: rationality.

The obsession with controlling the environment

Just as inborn rationality had always aided a child without them having every time to make laborious travels and putting one’s life at risk, it now helped the young adult homo heidelbergensis individuals. By deducting and abstracting, new adults could reach out far beyond their natural surroundings. They became faster and more efficient. Being intelligent and skilful, they were able to plan their actions and anticipate others’ as well. They were cautious because they could think of what was possible.

In lighter periods, they equipped themselves to be able to fight difficulties in worse times. They could notice that the most immediate and visible benefit was not always the best. They could wait for better times. But most of all, these emotionally immature new humans refused to give up and yield to nature like their adult fellow companions of the species. They were rescued purely by selfishness and prejudice. These were not new features, they had previously belonged to all adolescent individuals, but their dominance and prevalence were fresh. The prolonged care of the offspring could have favoured the stage of adolescence.

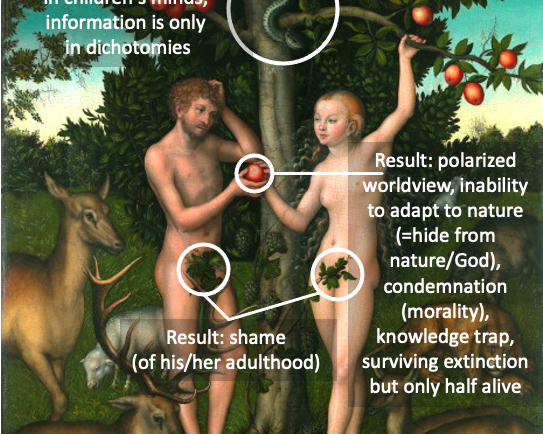

Therefore we can not say that we emerged as a new species. These mental features had existed for at least hundreds of thousands of years, so modern humans did not arrive with new capabilities. Those adolescent grown-ups who survived best from the natural disasters looked like adults but were mentally like teens. But as the adolescence of the population increased during the long African drought, the species lost their healthy feelings of belonging to nature. That was the cost of our survival and the milestone, which separated humans from other species.

Nature kept alive those who stayed the longest doubtful and questioning. These few individuals were mentally juveniles and reluctant to accommodate the threatening environment. This characteristic became the roots of our everyday humanity, its cause and originator. The birth of the immature human species generated in the African drought is the key to our feelings of loneliness and imperfection and our desire to master and highlight our uniqueness.

The sky may fall on our heads tomorrow

The desire to look at the weather, the natural signs and the celestial bodies resides deep in humanity. It is natural for humans to keep an eye on environmental changes and cope with their requirements. Every natural disaster exposes our highly obscure origins, our freakish emergence, our deepest fears and shame, the hidden weakness of our humanity, even if they were normal and natural alteration. If we cannot adapt to external or internal alterations, we will change the environment to survive and feel safer. That was the way we were born. And, for this reason, our hostile relationship with nature comes out quickly —mainly if it is supported.

Man is a herd animal, but his engagement is not the normal herd instinct of an animal. Instead, it is the fearful and selfish search for the safety of an immature, non-adult individual. What is pivotal to human herd instinct is individuality, which, paradoxically, is the similarity of all and even the competition for similarity. Living in large communities is not only protection from nature but has become more real than natural environments. It has replaced nature so that nature has become an unnecessary part of the world. Nature is considered a supply storage resource for human needs, the opposite of man, wild, domesticated, and even evil. It’s hard for us to see what’s wrong with this view.

We would certainly do it if we could change the weather just like the rest of our environment. However, nature has shown us that our fears only make our crisis deeper, not eliminate it. Nature works in a way that is far too complex for man to control despite all human knowledge. But we can also respect the weather and the environment. Respecting them means respecting ourselves—we are part of nature.