The emergence of humans is a mystery, with many unanswered questions about when and how our ancestors became like us. Despite piles of bones and stone tools, it is difficult to understand the course of events and the motives behind this evolution. Defining the onset of modern human behaviour is also challenging, with debates about whether it is characterised by stone tools or abstract thinking. The involvement of the mind means that bones and stone tools alone are insufficient to explain human evolution, making it a complex puzzle.

Crime scene: Stone age

The emergence of humans is a real murder mystery. The date, the course of events, and the motives are missing. Yet, we have a pile of bones and lots of stone tools, but they can’t lead us to understand when and how our hominin ancestors became like us. Another issue is what particular circumstance defines the onset of modern human behaviour. Is it stone tools or abstract thinking? And what is modern behaviour? Oh, why can’t the laws of evolution explain human evolution as easily as, say, finches! When the mind is involved, bones and stone tools are insufficient.

Scholars acknowledge that “the changes in brain size and shape that can be inferred from hominin fossils, unfortunately, do not provide clear evidence of the origin of modern behaviour.” We still lack clear evidence of it. Experts cannot confirm what exactly the tool-making meant evolutionarily. The appearance of stone axes does not seem to signify cultural change directly. The lack of evidence is generally linked to early humans’ lower level of development in symbolic language and abstract thinking. The history of human research sounds like the best murder mystery — there is no clue of motives or alibis. How can this be so difficult?

Despite its name, the Stone Age is not a geological but a technological and, thus, essentially psychological classification of the era. The Stone Age defines human activity, reflected in the end products of stone processing for about 3 million years; a proper geological period of nearly the same length is called the Pleistocene. It is still unclear where the tool-making originates and how it developed. It is a behavioural feature, and in contrast to the earlier behaviour, it is called modern behaviour. Scholars define behavioural modernity as a suite of behavioural and cognitive traits distinguishing current Homo sapiens from other anatomically modern humans, hominins, and primates.

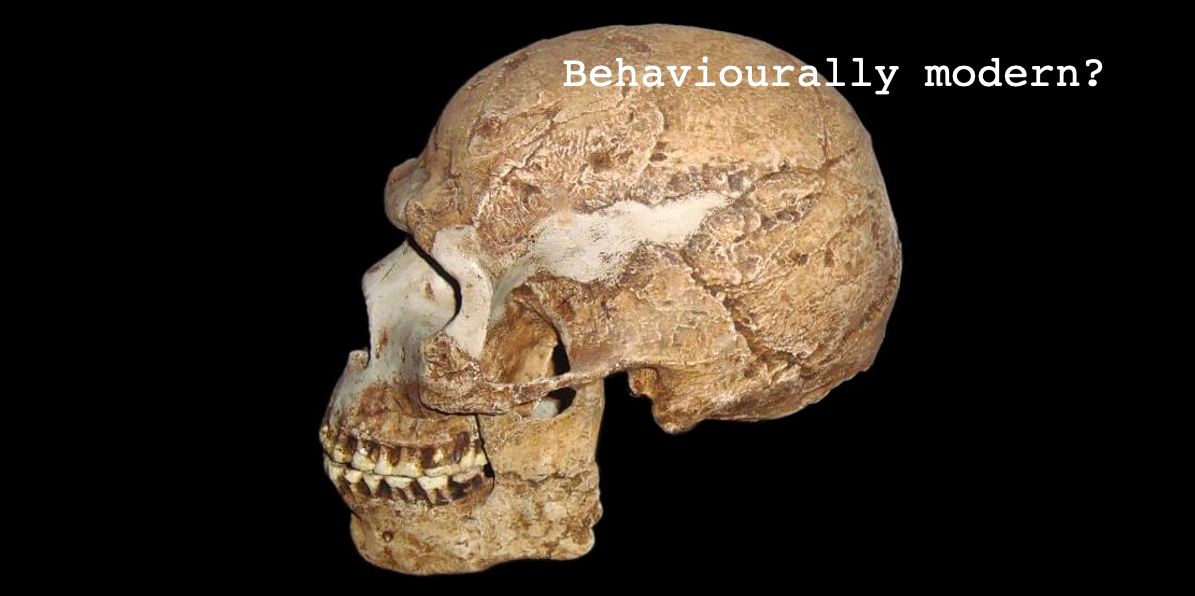

The debate continues as to whether anatomically modern humans were also behaviourally modern. The anatomically modern human, or early modern human, are terms used to distinguish Homo sapiens from extinct archaic human species. Early modern humans are, by definition, our ancestors who resembled modern humans who lived 300,000 to 30,000 years ago. Early modern humans are not a cohesive group or species but an umbrella concept that refers to several externally different and behaving members of homo populations. Modern humans are associated with appearance and behaviour, but most often in such a way that characteristics do not always coexist.

Strange behaviour

The simplest way to describe modern human behaviour could be, for example, by tool-making (stone and bones), dispersal of populations, and the use of fire. Many other characters are also listed, such as burial, fishing and figurative art. Features may not occur all at one time. Behavioural modernity is based on observations to give direction to theories that explain the unique history of human development.

The expression focuses on human behaviour, the mind, and psychological factors, while the Stone Age sees man only outside. However, the mind has played a relatively minor role in archaeological research. That is not unreasonable because the mind does not remain in the sediments of the soil.

How could modern human behaviour be observed more than two million years back when there was no modern human at that time? The Stone Age began two to three million years ago by making the first stone tools. The oldest indirect evidence of stone tool use is fossilised animal bones with tool marks. These fossils are up to 3.4 million years old and were found in the Lower Awash Valley in Ethiopia. Stone tools over 3 million years old have also been found in Kenya. So the oldest toolmaker could be this Kenyanthropus below, an early ancestor of humans. But was he a modern human at all? Hardly. Is this the ultimate reason we have many different concepts describing the same thing?

The Murder Weapon | Man takes the tool-making so for granted that he defines entire eras accordingly. First, scholars say tools are sporadic for many homo species but are critical for modern humans. Understanding what such a difference means is good because it is a clue. Second, they say there is no going back to the ages when tools became necessary. It is a good observation and most undeniable. That conceals the implicit assumption that modern humans are evolutionarily maladapted because they cannot survive without essential survival tools. And if they are maladapted, they are not a creation of natural selection, for only natural selection can produce adaptations. That is another key to the mystery of modern humans.

The concepts refer to the same thing, but they have different perspectives. The Stone Age draws attention to tangible artefacts. “Anatomically modern” seeks an explanation for physiology and human manifestation. Modern behaviour, for its part, focuses on the psyche and its changes. The debate between the views relates to how archaeological and paleoanthropological discoveries support modern behaviour and when modern behaviour has begun. Was it born during the time of the Out-of-Africa Migration or earlier? The problem is probably more complex than it looks.

“There is no straightforward relationship between the appearance of particular archaeological signals of modern behaviour and certain kinds of fossils. Some see the development of modern behaviours as a late phenomenon, dating to 50,000 years ago, not related to the speciation of anatomically modern humans (Klein 2009). However, many archaeologists associate the development of modern behaviour with anatomically modern humans or Homo sapiens who emerged in Africa around 200,000 years ago, during the Middle Stone age period. The picture is not clear, as modern behaviours have also been linked to the Neanderthals of Europe and hominin ancestors living prior to 200,000 years ago (Deacon & Wurz 2001, Zilhão 2007, d’Errico et al. 2009, d’Errico & Stringer 2011).”

Formal investigation

From a scientific point of view, “modern behaviour” is a “working hypothesis” created based on exceptional observations to define something that scientists cannot deduce from current theories. Modern behaviour is, therefore, an anomaly. Anomalies are observations that differ from the prediction given by prevailing theories, either qualitatively or more than what is appropriate for the margin of error. Making tools, let alone symbolic language or abstract thinking is an anomaly in the evolutionary framework. No such purposeful activity can be found in any other being.

It is typical research to protect paradigmatic science, that is, to loosen the rule so there won’t be room for exceptions. However, this has not been entirely possible with tool-making. Another way to overcome anomalies is to show how, when “correctly understood,” they don’t break the rule in question. Unfortunately, that often leads to so-called “ad hoc” hypotheses, which hide unexpected and exceptional things rather than open them up for research. Ad hoc hypotheses compensate for anomalies not anticipated by the theory in its unmodified form.

Mastermind is a popular code-breaking game, the idea of which is to find out the colour code behind the shield within the given turns. It is based purely on logical reasoning, the same as scientific reasoning. However, the broader the issues, the less often the scientific reasoning is logical. That is obvious, especially in the studies of the emergence of modern humans. In Mastermind, it is possible and essential to use deductive and abductive reasoning. Abduction could be seen as “the logic of invention”. It is applied when no direct traces can be found, as is often in anthropology. Although deduction is often considered the most reliable scientific reasoning, it only tells what is evident in the premises. However, it is not always “desirable” to “see” everything obvious in science. In cases of anomalies, scientific procedures may violate the principles of reasoning if exceptions are not accepted as premises. Game-wise, the player (science) can not instruct the code creator (nature) on which colours are allowed.

From the point of view of scientific consensus or consilience, this may lead to the rejection of opinions conflicting with the prevailing paradigms, even if they were correct. The situation is most typical wherever single attention or opinion violates scientific paradigms. The academic research of anomalies generally supports the prevailing scientific status quo. So, there is more to the game than the facts: authority, prestige and money. In politics and science, the majority always holds the keys to the truth, so the minority, not to mention individual researchers, is allowed to settle for it. Scientific thinking does not favour grudging individuals, and often not even those with more answers than questions. In theoretical research, questions are often more important than answers, or at least they seem more professional.

Breaking the code

Although there is disagreement about whether the behaviour in Early Stone Age can be called genuinely modern, the complex human abilities and skills were still visible in early humans. As mentioned, we should know what particular circumstance defines its onset to understand modern behaviour. It seems inevitable that it is tool-making, even though it will take millions of years to develop. The size of the human population has averaged only about one million individuals worldwide until the end of the last ice age. That suggests that a small and isolated population would produce less cultural variation than a larger and interacting population. For example, chipping stone axes could generate new creativity only through interaction. The most primitive tool-making and complex machines would be equally modern behaviour. The variation would be due to the environment or, more specifically, the size of the population.

That does not solve the problem; it only defines the temporal framework of modern behaviour. We still miss the clue between the modern behavioural features of different eras. What connects Homo habilis chipping off flakes with another stone to a modern human who does the same? If “modern behaviour” is not the cornerstone of modern humans, what does it represent? Research has found none, creating the umbrella term of behavioural modernity. But, of course, the unifying factor does exist, although it is difficult to find. Maybe we are looking for it from the wrong direction, or our conclusions are wrong. We know the trait superseded other features and eventually eliminated the older variant.

Researcher making a stone tool | Tool-making is modern behaviour’s first and most apparent sign. The appearance of the first tools can be scheduled around 3 MYA. However, it is unclear what kind of mental change tool-making indicates, where it came from and why. Furthermore, what kind of genotype or phenotype is it? Examining stone tool techniques alone cannot answer these questions. Therefore, the focus has to be shifted to studying the early human mind rather than the interaction of the hand and eye.

Behavioural modernity shifts the focus inevitably from fossils to psychology. It means a question of how we will define this unifying factor. But modern behaviour has only been named so far; we must also explain it. We cannot think of it as the behaviour of modern man alone because our tool-making ancestors were not physiologically modern humans. Therefore, the term “modern” usually includes the assumption that the behaviour it defines gradually evolves from primitive to more complex forms. Specific traits that were incidental in the earlier human species somehow accumulate in modern man. But what unites the tool-making, the language, the clothing, and the use of fire? What connects us to the early toolmakers?

We can open up the problem also through genotypes and phenotypes. The genotype is the complete set of the organism’s genetic material, while the phenotype is the set of observable characteristics or traits. For example, we could assume that the new toolmaker genotype about 3 million years ago will appear as a modern phenotype in later studies. However, because the environment influences the phenotype, the same genotype may not manifest in the same way in warm Africa as in cold Europe. Thus, the early phenotype might differ from the latter. Even though we cannot accurately see three million years back, the complex features must undoubtedly have been latent. In any case, the tool-making phenotype is a behavioural expression of the abnormal genotype.

Using fire is part of the same modern behaviour phenotype as making stone tools. New behavioural expressions emerge at different times due to external circumstances and mainly to the interaction between atypical individuals.

What created the expression of such behaviour? There had to be a personal need behind the making of tools. I mean, it was not a species trait but an individual quality. Had it been an “ability,” as is often argued, it would hardly have been used two million years to chop stones. The personal need for tool-making feels probably the same as today: individuals want to protect themselves from the outside world by anticipation. But why would such a trait suddenly and without warning appear? The reason could not be the cooling of the climate, as the earliest signs of tool-making can be found in Africa, where the ice age did not extend. Tool-making is not a spontaneous response to external circumstances but planning and anticipation. It is a change in the psyche characterised by abstract thinking and planning depth already at its birth. Other features will follow as soon as interaction gets a chance. Toolmaker is an exceptional individual who doubts and doesn’t just trust his luck; he wants to make sure. He is not entirely familiar with his surroundings and feels separate for a reason he does not understand. A sense of isolation suggests a problem in mental adaptation.

From the frequency of stone tools and their few traces, it can be concluded that the genotype may have been shaped, for example, by a recessively inherited genetic defect. The genetic defect hardly affected the desire to shape stone tools alone, although no direct evidence exists. Still, it seems possible that modern behaviour has been an influential factor in sexual selection for at least a million years before homo species. If so, it may have indirectly accumulated “favourable” anatomical features for modern behaviour. Mentally adolescents avoid archaic or adult phenotypes and thus tend to favour childlike traits in their partners. They are coded to shun adults, nature, and instincts. The increasing juvenile qualities were therefore reflected in the offspring over the millennia. The results appear not only in behaviour but also in physical appearance. The face flattens, the forehead becomes higher, the chin narrows, and the eyes are accentuated. The intensity of development depends mainly on the size of the population because a large population means more exceptional individuals.

Manifestations of modern behaviour, such as graphic works (“art”), emerge only through a gradually expanding collaboration and interaction, even though they are part of the original phenotype.

According to scientists, modern behaviour was widespread roughly 50,000 years ago. This behaviour was a rare exception for a few million years before that. The recessive nature of the feature has always kept its carriers a minority. It never before became a species trait. Homo populations were always divided into mainstream adapters and a minority of abnormalities. However, only the latter left their mark on posterity. Therefore, the archaeological evidence will not tell about the whole species but only the exceptional individuals. Almost all theories related to human development seek to connect archaeological material to the entire species and therefore fall into a dead end. For example, qualitative differences in tools are insignificant, although they are often invoked to refer to the graduality of our mental development. But only the tools evolve, not the mind behind them. Therefore, the relationship between tool invariance and population size is more critical than the grand illusion of the development of the human mind.

If we think that such a history of a trait could suggest a genetic defect, then we have a hypothesis for which we can begin to seek support from research. Moreover, a genetic defect can be unifying because it can occur unannounced, inherit, and explain similar traits in temporally distant individuals. But where does it come from, and what is it related to?

The lead

The roots of modern behaviour could be sought from many directions. However, it is no coincidence that modern behaviour is what it is. Allegorically, the traces lead to “a dark alley” that scholars have overlooked in this context. And no wonder—there are only children in that darkness. Children are almost entirely ignored as the subjects of these studies. Indeed, it seems evident that all those exceptional qualities that we consider “abilities” and understand as “modern behaviour” are initially children’s behaviour. It is functionally part of the child’s psyche to be just that. Abstract thinking shields a weak and developing child against immoral nature. The child has the capacity for abstract thought and planning soon after birth because nature can be dangerous for him. His world is theoretical for protective reasons. Everything in him is highly controlled because of that. He is inherently sceptical and prejudiced, even though suspicion will soon be counterbalanced by curiosity.

However, he is not entirely familiar with his surroundings because his psyche keeps him away from trouble by force. He is unfit in nature, but for a good reason. An archaic child could have adopted the entire behavioural modernity if he only had role models. But they were scarce. Civilisation associates these qualities only with mature adults, but the fact seems to be that they are characteristics of immature children. Rational thinking, willpower, abstract thinking and planning, speaking, writing, artistic creation, morality, resentment, justice, warfare, development and progress, and isolation from nature are rooted in children’s early development. These had absolutely no function in the life of archaic adults. The worldview of civilisation is thus wholly on its head. Unfortunately, science does not feel the slightest desire to show it. Truth is a metaphysical concept, indeed.

The next question reads: once modern behaviour is a healthy trait in children, how can it become a sick trait in adults?! Understanding this requires a new hypothesis. The hypothesis is related to mental growth and its radical change during adulthood. Modern science does not recognise the difference, so it cannot explain human emergence either. In the pre-human era, children’s psyche changed when they became adults. Now there is no change. During the Stone Age, the ratio between normal and infected/exceptional individuals varied. The variance was due to the gene allele that prevented the onset of transformation in infected individuals. Presumably, the change in the psyche used to be the latest in a series of changes related to growing up into adulthood, ending the entire childhood/adolescence phase. Now individuals grow physically into adults but remain a child/young mentally. This fault is permanent and fatal. It causes many problems such as maladaptation and fear of death that healthy early humans never faced.

Modern behaviour, when intensively propagated, seems to be colossal advancement, but evolution-wise it means a recession, a sickness, as many indigenous peoples claim. Humans’ position is not above other animals but below them. That is a pure fact. Modern behaviour represents a phenotype that seeks to isolate itself from nature and thus from natural selection. Modern behaviour is the result of an ancient genetic defect. The spread of modern behaviour (in science, “human evolution”) means more genetically defected individuals in populations. The weakness is no harm when it occurs infrequently, but as it appears more often, the damage to other creatures and the environment increases. Detached from nature, humans become indifferent and fearful, quickly becoming beasts and killers.

The syndicate is revealed

We must still understand how exceptional and recessive features become universal and prevalent. Genetic defect alone is not enough; it only gives it a chance. But it still needs an opportunity to spread! This opportunity only occurs after the hereditary defect has existed for 2 to 3 million years. We know that the Heidelberg people (or Homo bodoensis) ended in the same environmental catastrophe in which modern man emerged. What a coincidence! The tragedy was devastating climate change dated to the African drought caused by the Saale glaciation; the glaciation peaked about 150,000 years ago but ranged from 300,000 to 130,000. That meant the long and slow elimination of the Heidelbergs.

A crisis is always present for modern humans because they were born in an environmental catastrophe.

The species drifted to the brink of extinction while its genetic variation narrowed in the process. Usually, the narrowing of the genome is a negative sign, but now it strangely prevented the species from being destroyed in the drought. What happened? The emergence of modern humans and the extinction of Heidelberg do not coincide by chance. A couple of points are apparent. First, the extant and extinct had to be of the same species and, therefore, modern humans are not exactly a new homo species. Second, the strong instinct for self-protection inherent in children was critical for survival. The survivors were more determined and creative. Therefore, the survival of the few is not a question of natural selection or adaptation. Homo sapiens emerged when there was no more archaic behaviour in the population. Third, if natural selection could not affect the new defective phenotype, it could not affect its genotype either. The only evolutionarily affecting mechanism was genetic drift which only narrows the genome. Fourth, the homo species in question should have been extinct.

This is the way modern humans are linked with early toolmakers. Human survival results directly from the state of mind we have today—the mind that is more distressing than we dare say. We have to pay a heavy price for it. We live in overtime. A life without a healthy connection with nature is a curse. Man’s endless wonder about his existence, the need for spirituality and the supernatural, his fascination with intoxicating drinks and narcotics, and the pursuit of higher above everyday agony are fully justified, as these traits tell us about the fundamental shortcomings of our nervous system. Civilisation and high culture have tried to cover up and sublimate the real causes, but these constantly emerge with new generations. The mental puberty of all adults is the absolute taboo of humanity.

Evidence

Childhood/modern behaviour is, of course, an ancient trait. For millions of years, child behaviour used to disappear after adolescence. Still, for reasons unexplained so far, it looks to become a permanent feature in some few individuals 2–3 million years ago. That is reflected in the archaeological data as the appearance of stone tools. Archaeological data can also be used to conclude that modern behaviour could be a genetic defect and an inherited trait. However, a genetic defect might not be as young as, for example, Richard Klein and Blake Edgar present in their book The Dawn of Human Culture (John Wiley & Sons, 2002), i.e. 50,000 years.

That late onset of a genetic defect cannot explain the features of modern behaviour that existed before modern humans. During the Middle Paleolithic, evidence increased sharply, indicating that defected individuals (subject to modern behaviour) were intensely opposed to change, unlike normal adults. On the ground, the defective coped better with environmental challenges than normal individuals and thus gave them better chances of reproduction. Their number increased further under favourable environmental conditions, displacing normal individuals by about 50-70 kya. Resistance to change is still a key behavioural feature of modern humans.

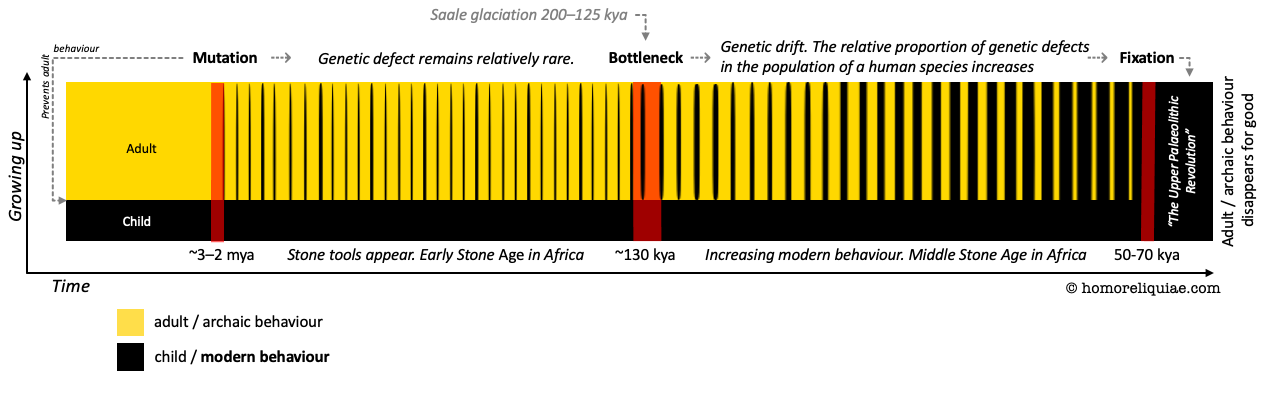

Modern behaviour as a 2–3 million-year-old genetic defect | The diagram above (click to enlarge it) illustrates the emergence of modern humans as the disappearance of archaic behaviour. The black lines depict the archaeological findings and their hypothetical frequency. Black bars and lines also represent the behaviour of children and modern adult humans, whereas yellow areas indicate archaic adult behaviour. Behavioural modernity (black) began at least two million years ago and possibly even three million years ago. Behavioural modernity is, therefore not very modern, not at least operatively. Its manifestations remain relatively constant for a couple of million years. After that, they increase until the original archaic behaviour is eliminated, about 50-70 kya.

Contrary to what has been argued, modern behaviour is not born 50-70 kya. Instead, at that time, it finally terminates the alternative variant. It is also noteworthy that the archaeological heritage cannot be classified as the “culture” of the species until about 120 kya, and not entirely even then. The archaeological findings can be called a culture only when most of the population can participate in its production. The date for this is difficult to determine, but it is at the latest after the so-called fixation, 50-70 kya. We should call all earlier signs of modern behaviour exceptions; they do not represent the entire population or the cultural understanding of the whole population. The bottleneck in the diagram means genetic drift. It should also have signified the final extinction of Homo bodoensis. Still, a genetic defect inherited from previous homo species allowed defective individuals to survive, whereas the mentally normal population perished.

Can we close the case?

First, it is essential to understand that all manifestations of modern behaviour result from one particular phenomenon. It is millions of years old but still not a common feature of pre-humans or humans before 50–70 kya. Therefore it is also not a new feature. Initially, it was not a species trait but a feature of all homo children. It is difficult to say whether it later became a species trait but a widespread disease. We can explain the behavioural variety by the fact that the larger the population, the more active the interaction and the more creativity comes to the fore. Only tools evolve, not the mind. The small population practically means a low incidence of new inventions. The evidence suggests that the genetic defect could not spread to the entire population in normal conditions. Likewise, before modern humans, tool-making could not be exhaustively taught and applied to the whole population. Learning is only characteristic of a part of the population.

Second, modern behaviour is not dependent on brain size and thus is not directly related to the brain. It’s not about adult abilities, although scientists so stubbornly claim. One needs to be careful in the direction of the causal relationship. Although language undoubtedly developed with the brain, that is not the whole picture. It isn’t easy to see if symbolic language is considered an ability. Namely, it is difficult to explain where it comes from unless there is a change in the brain. But because modern behaviour emerges just as suddenly as one can imagine, it cannot be a product of gradual development. Or more precisely, modern behaviour is not just about language, tool-making, dressing, etc., but about how these characteristics are preserved from childhood to adulthood. We can not identify the failure because adulthood is a seamless continuation of childhood. To determine the malfunction, we need good luck to notice the mental change that occurs only very rarely.

Things that have been innate and self-evident to human children for millions of years turn into mysteries when applied to adults. Admittedly, it took a long time before the adults adopted the habits of the children. However, understanding this abnormal development is the key to understanding the stages of modern behaviour. Working hypotheses such as the “executive function and working memory model” from Thomas Wynn and Frederick Coolidge is per se in the right direction but practically irrelevant. Working memory is the mind’s ability to hold information for complex tasks. Executive function encompasses the brain’s ability to plan and strategise. These have been latent characteristics of all homo children for millions of years and, thus, by no means new features. We think cognitive functions such as planning and learning are complex because they indicate the mind’s ability to focus on, store, and manage information temporarily. But will their glamour disappear if they tell us nothing about adult individuals and human development? Perhaps so.

So, modern behaviour is more of a disease than an ability. It cannot be defined as a brain product or a completely new phenomenon. It is none of these. The only way to explain the emergence of modern behaviour is to understand it as a continuation of childhood behaviour made possible by a genetic defect. Therefore, the mystery could not be solved by studying modern behaviour alone, but also archaic behaviour and how it became displaced. Moreover, modern behaviour confuses scholars with its species’ trait-like nature. Therefore, behavioural modernity is more of a disguise of illness.

Lost in criminal archives

Modern behaviour cannot be understood without archaic behaviour. It is essential. Although it does not occur anymore, it has left trails on indigenous worldviews, world religions, mysticism, and art, among other things. The account of Adam and Eve is possibly the very first written version of the emergence of modern behaviour. The story is not credible if it is taken literally. But a proper private eye can read between the lines. The story is an excellent attempt to explain the emergence of modern behaviour. Adam and Eve are the symbols of the human species. The first couple refers to the essential role of heredity. Just as Adam and Eve are described here, in the case of the human species, part of the population was hereditary normal, and part was not. Given the limited scientific knowledge of its time, the description is apt. It supports our report as it considers modern behaviour an accident caused by man himself. It even describes the genetic defect as a serpent that offers Adam and Eve immortality. The serpent allures humans out of nature, that is, out of paradise. Man’s sin was only to accept the temptation not to die. Indeed, the human species was saved from extinction precisely because of genetic defect. The thing I have defined here as an illness, or mental adolescence, is described as a judgment of God (nature) in the story. However, Eve could not fail to offer Adam ”the fruit”, and Adam could not fail to ”taste” it when it comes to hereditary matters. Even though the story says nothing about growth, it should be understood as a symbolic account of actual evolutionary events, not a fable. The story is probably much older than the Bible and tells a lot about the wisdom of the era.

Religious people sometimes also speak of rebirth and enlightenment. But, of course, we should not understand these spontaneous expressions literally. Unknowingly, however, they seek a solution in the minds of an archaic human. Rebirth can thus be understood as abandoning modern behaviour that happens accidentally in mystical experiences.