The expansion of modern humans from Africa through Asia to Europe and the rest of the planet marked the beginning of a new kind of life on Earth and the final loss of a traditional way of life of the homo genus. The homo species were a game for the animals for a long time, but after learning to make tools and communicate, people became hunters. The control of their surroundings gave the adolescent Heidelbergs new life opportunities and made them realise their stronger position in the wild. It wasn’t just the case with its northern cousin, the Neanderthal man, whom the young intruders confronted around 35,000 years ago as they entered its European district. When this historical confrontation ended, the Neanderthals had vanished. Today, our closest living relatives are chimpanzees, with the help of which understanding human development, despite intense research, is almost impossible. Thus, understanding human nature must begin with the Neanderthals, even though this research is, to a great extent, imaginary.

In Neanderthals, the newcomer Cro-Magnons faced non-talking and ”stupid” relatives akin to their ancestors. Dark and long Cro-Magnons differed clearly from the muscular and stout Neanderthals who were adapted to cold climates, but the actual and determining differences between these species were not visible at all. They were not directly related to length, skin colour, or the brain.

Neanderthals lived quietly without leaving a trace for as many as 250,000 years. They had a smooth and trouble-free relationship with nature, as with the Heidelbergs before the devastating drought. But the Cro-Magnons lived continuously dissatisfied, travelling and shaping their surroundings. As a result, their relationship with nature hasn’t been straightforward and uncomplicated for a hundred thousand years.

This Channel 4 Neanderthal documentary from 2001, despite its many shortcomings and inaccuracies, opened my eyes to an understanding of the strange psyche of modern man. I realised that the altered states of consciousness were remnants from the psyche still carried by the Neanderthal man. I realise that my view is at odds with modern scientific knowledge, but it explains the psyche of modern humans better than that.

For a reasonably inconceivably long time, i.e. from two to three million years up to the appearance of the modern human, the life of homo species was trouble-free coexistence with nature, even though it was perhaps difficult. It figures in the few footsteps these people left behind and gives rise to a feeling that they haven’t been able to human intelligence, language, skill, or desire to modify their environment. They made tools but did not develop despite the tens of thousands of years of use. Richard Leakey wrote about Neanderthal tools that when the new technology was well established, it didn’t change. Instead of discovering new things, constancy was characteristic of the new era.

The same also applies to Neanderthal men. The constancy relates to the small and random number of adolescent grown-ups and their insignificance in the homo populations. Like the previous species, Neanderthal humans were not supposed to grow intellectually. However, they were neither stupid nor underdeveloped. Neanderthals would not have changed even now if they had been able to live. They would still not be social, speaking, or living in contact with modern humans.

We, modern humans, tend to depreciate our early ancestors. At first sight, we humans may look more advanced than, for example, the homo ergaster, but we have begun to realise that such an evaluation of development by the look is unreliable. Neanderthals may look like mere ”cavemen, “ yet this austere, reticent and non-erotic relative of Heidelbergs exposed our archaic and mystical past like it was until it disappeared in Africa’s disastrous drought. Then, it is possible to reconstruct it. With the help of imagination, we return to the yet-forgotten realm of the ancient mind.

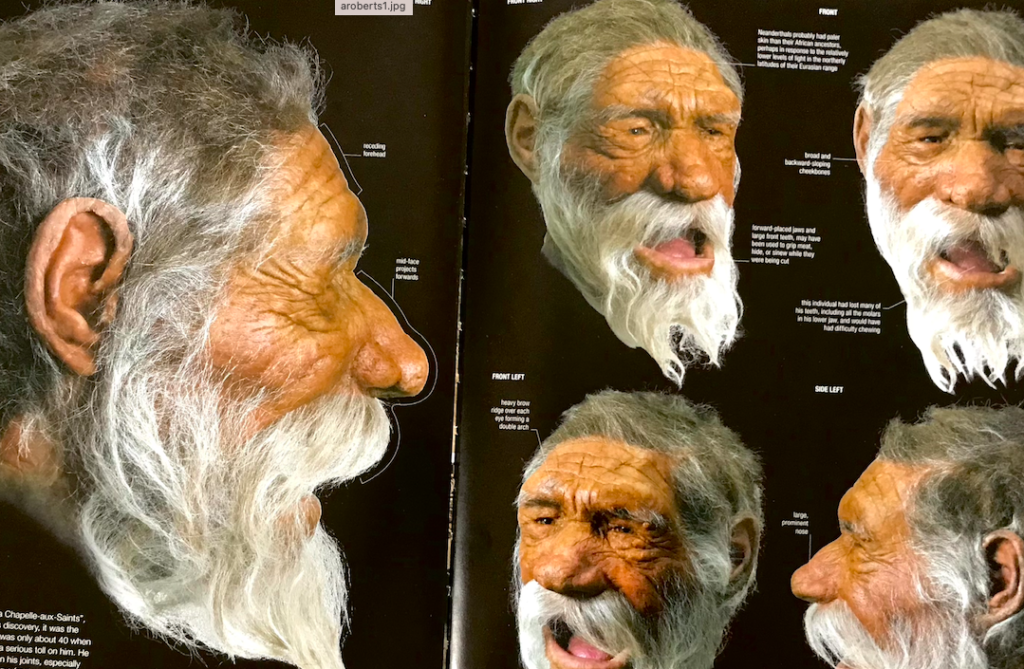

The reconstruction of the Neanderthal man’s head is based on the discovery called the “Old Man of La Chapelle-aux-Saints”, which is thought to be about 60,000 years of age. The photograph is part of pages from Dr Alice Roberts’ book Evolution, The Human Story.

Everyday life

Everyday life? Well, let’s imagine it based on things we know already. Neanderthal knew fire and simple tools. It made stone scrapers and axes by chopping slates out of flints. Tools didn’t change in the course, which has lasted up to 100 times longer than our civilisation. Undoubtedly it hunted small game, but bigger ones it acquired instead as carcasses. It fought in cold and harsh conditions with predators to get carrion meat, fried on fire or eaten raw. It may have used herbs and plants to heal wounds and bruises, but there is no certainty. There are no signs of dwellings, although the species drifted through the same areas even thousands of years. It usually stayed in caves and other cotes in the wild. Because of the continuous cold, it dressed in skins, the habit it had adopted from its adolescent fellows of the species.

He lived calmly with a small group of his familiars. He was not interested in the other representatives of the species—not to mention the modern man—and did not contact them. He didn’t know the boat or other vessels or how to move over the water. He might have had his familiar environment and the old turf on some riverbank in contemporary Germany, France or Belgium. He had undoubtedly defended it but did not know war like any human species before modern man. The Stone Age tribes were probably already warring together, but the Neanderthal man could not because he could not plan collective action.

We can not understand the Neanderthal people because the term ”understand” is entirely unsuitable for the species, for which rational thought is not as critical as it is for us. However, we can study his mental life and see something in common with ours. Although ”mental life” can sound too excessive an expression of the Neanderthal’s case, it may unexpectedly be too modest. In any case, the consciousness familiar to modern humans is not a typical characteristic of adult Neanderthals. We cannot find the intense need for making questions anywhere else in the fauna as with humans. Some researchers want to see the language, symbols, sex or war as a foundation of modern humanity, but we may ask, what kind of individuals do we get if we remove these qualities? Such a study is worthless because the explanation has an apparent circumstantial conclusion. To see a Neanderthal man as a basis of our ancestors, we need to strip a fundamental quality from modern humans: the ability to ask questions.

Strange mind

If the Neanderthal and the earlier homo species could not make questions, they also lacked the rational thinking characteristics of modern humans. All rationality of the Neanderthals can not be ruled out because many animals are capable of it. They assess risks, for example. Young individuals have had more vital rationality than grown-ups. The reasoning was also needed to make a fire and deploy the first tools, which probably occurred a few million years ago. But we can quickly notice that, compared with the rationality of modern humans, the rationality of our earliest ancestors was slight and as if it would have been in use only a tiny part. Lack of rational thought, of course, meant a lack of concepts. It probably did not prevent simple thinking, but indeed the language. I am convinced that the Neanderthals made sounds but could not speak, even though many believe so.

Running into Neanderthals, Cro-Magnons encountered their very own past, even though they hardly recognised it. If modern humans had developed like the previous homo species, they would have been equally behaving and experiencing. Now they were significantly different from Neanderthals. We should imagine the Neanderthals as an adult version of the Cro-Magnons. And I am now going to conjure up both the early Heidelbergs’ and the Neanderthals’ inner world by disconnecting the previously mentioned immature features out of the modern human, i.e. undressing our childish mental appearance. My intention is, therefore, a reconstruction of human adulthood. Although it is pretty difficult to picture, adulthood is the most sacred thing imaginable to modern humans. It is so because we have lost it. Not for good, it is still experienced by some, though the number of those people is relatively few. It means a brief loss of will, but, as you may note, this is not how most people apprehend it. However, I want to describe it like that. So I try quite impossible: to tell the reality of the homo genus as it was in the distant past. Nevertheless, I have a better chance than those ignorant of this rare, strange prehistoric phenomenon of becoming an adult. Therefore, in contrast to science in general, I am confident I can enter the challenge entirely subjectively.

This reconstruction of the Neanderthal man gives, in my view, an erroneous picture of the species. This man strongly embodies modern human traits with his facial expressions, trimmed beard, hairband, and tattoos. However, it is hard to believe that Neanderthal man as a species bore such characteristics. Although the few individual members were mentally much like modern humans, they were rare exceptions. Traits and habits only emerge when there are enough individuals of similar mentality in the population. Therefore, humanly thinking individuals in Neanderthal communities were always uncommon. Therefore, if we want to highlight the strengths of Neanderthal man, we should not do that by adding human qualities to it. On the contrary, the occasional human-like features of the species (stone tools) were weaknesses that were not part of its actual nature. Although modern humans see the manufacture of tools as a sign of development, it is not from evolution. (This reconstruction is on display in the Natural History Museum, London.)

There were many more features the Neanderthals did now own. They were unfamiliar with laws, rules, standards, recommendations, prohibitions, commands, orders, requests or prayers. They felt no necessity or possibility. They did not plan nor discuss the options because they were none. They were not unhappy because they were not familiar with intention, will or desire. In this sense, they were not active. They did not distinguish series or chains of events or create connections between them. They did not know purpose, goals or ideas. They did not explain anything because they did not recognise the causes. They did not try to understand because they did not need that. Therefore, they had no problems at all. They didn’t classify or separate things— not people, animals, things, acts, times or even places. They did not know inequality because they did not identify values, morals or superiority or inferiority rates; instead, they did recognise the true usable things. For modern humans, it is difficult to find something more moral than equality, but for the Neanderthals, things were even more than equal—they didn’t compass any values to compare. The Neanderthals also had no roles or games. They were not familiar with humour, joke, satire or comedy. They didn’t sneer, fool or lie.

The Neanderthals did not write, read, draw or, as likely as not, talk, although they certainly made noise. They didn’t distinguish characters as symbols but knew how to interpret the signs and signals of nature their way. They did not build nor isolate themselves from nature. They did not imagine themselves as a species. They belonged to their surroundings. They did not want things like modern humans; they acted spontaneously. Probably they had dreams, doubts and wonders, but they didn’t think with concepts because they had none. They knew no family or parenting, no home nor relatives in a sense how we comprehend them. They avoided apparent dangers, not because they wanted to be protected, but because they sensed that. They were not afraid of their surroundings. They did not compare things to see something on the outside, but the items themselves. They did not learn or feel like individuals. Therefore, they were unfamiliar with identity or ego as we are.

However, we can say something about the Neanderthals without negations. They knew something we might call intense experiences. They also accepted the world they faced without question—they did not have to take any action. Even with all the resistance and imperfections, the world was ready and complete for thems. All setbacks and deficiencies were equally part of the world, as was nature generous to all senses and needs of its children. They felt interested in the being itself in all of its austerity and simplicity. They were interested in everything they faced, but not because of their mutual relations or connections, just because of the items themselves. They knew how to help their fellow species, although they didn’t feel sorry for them. The Neanderthals loved to live, and they did it sincerely and wholeheartedly.

This reconstruction of a Neanderthal man and a woman also depicts the Neanderthals as too human. However, it is essential to realise that the tool making divided the species internally. It was by no means characteristic of the species but only of a few individuals. Image credit: Neanderthal Museum.

A bit of poetic licence

There are no scientific studies of the mind of Neanderthals, and we can not know for sure what they were like, but we can construct a hypothesis to test options. We should pursue testing to learn that archaic adulthood was quite different from what we think is mental maturity.

The Neanderthals had none of the dominant neotenous features characteristic of modern humans. They did not have language, truths, gods, religion, time, identity, the desire of owning or deceiving or warring or a fear of death. The Neanderthals did not rebel, not complain, not mourn, not be delighted, not hated, or get indignant. They did not store things nor get equipped for, did not wait for tomorrow and did not live in the past. They did not regret nor celebrate their success. They did not fall in love, have beliefs of any sort, hope, be delighted, get tired or bored or lust for things. They didn’t decorate themselves or their surroundings because they didn’t feel ugly, beautiful, happy or sad. They didn’t know the pleasure or the annoyance, even if they felt the pain. They copulated but didn’t know sex or shame.

The Neanderthals lived in the moment because they did not understand time. Therefore, they didn’t know recent years, not next year, or weeks. They did not realise feasts or fasts and could not distinguish the holy from the routines. They did not know what soon or recently meant. Every moment meant living, action or resting. They recognised the young and the old, but not the age. They did not want a change, even though things were terrible; things were as they were.

They did not want to improve things for the same reason: there was no reason. They were cold or hungry when they were cold or hungry, but they did not suffer. They did not blame or criticise anyone or anything. Nor were they vengeful because they felt no injustice or justice, fairness, sin or crime, redemption, forgiveness, goodness, or evil. They did not pray because they were unfamiliar with gods and devils, heaven and hell. They knew no mysteries, magic, magic tricks or secrets. They knew no lies or truths, no covering up nor revealing. They were not familiar with profit or loss, even though they saw death. They felt no nullity or weakness but no greatness either.

Researchers have argued that the Neanderthals believed in the afterlife and buried their deceased. Even if some believed such, and even if individual burials had taken place, the Neanderthals did not show such thinking. Again, it is crucial to understand that the actions of some individuals did not reflect the features of the species as a whole. The differences were due to a rare inherited mental defect in some individuals.

There were many more features the Neanderthals did now own. They were unfamiliar with laws, rules, standards, recommendations, prohibitions, commands, orders, requests or prayers. They felt no necessity or possibility. They did not plan nor discuss the options because they were none. They were not unhappy because they were unfamiliar with intention, will or desire. In this sense, they were not active. They did not distinguish series or chains of events or create connections between them. They did not know purpose, goals or ideas. They did not explain anything because they did not recognise the causes. They did not try to understand because they did not need that.

Therefore, they had no problems at all. They didn’t classify or separate things— not people, animals, things, acts, times or even places. They did not know inequality because they did not identify values, morals or superiority or inferiority rates; instead, they did recognise the true usable things. For modern humans, it is difficult to find something more moral than equality, but for the Neanderthals, things were even more than equal—they didn’t compass any values to compare. The Neanderthals also had no roles or games. They were not familiar with humour, joke, satire or comedy. They didn’t sneer, joke or lie.

The Neanderthals did not write, read, draw or, as likely as not, talk, although they certainly made noise. They didn’t distinguish characters as symbols but knew how to interpret the signs and signals of nature their way. They did not build nor isolate themselves from nature. They did not imagine themselves as a species. They belonged to their surroundings. They did not want things like modern humans do; they acted spontaneously. Probably they had dreams, doubts and wonders, but they didn’t think with concepts because they had none. They knew no family or parenting, no home or relatives, how we comprehend them. They avoided apparent dangers, not because they wanted to be protected, but because they sensed that. They were not afraid of their surroundings. They did not compare things to see something on the outside, but just the items themselves. They did not learn nor feel like individuals. Therefore, they were not familiar with identity or ego as we are.

However, we can say something about the Neanderthals without negations. They knew something we might call intense experiences. They also accepted the world they faced without question—they did not have to take any action concerning it. Even with all the setbacks and imperfections, the world was perfect and complete. Accidents belong to life, too. They felt interested in being itself in all of its austerity and simplicity. They were interested in things because things were fascinating, but not because of the mutual relations or connections things possibly had. They knew how to help their fellow species, although they didn’t feel sorry for them. The Neanderthals loved to live, and they did it sincerely and wholeheartedly.

We usually either belittle or humanize the Neanderthals, but neither is correct. The connection Neanderthals have with modern humans is religiosity! The human “enlightenment” is, in fact, Neanderthal’s normal and permanent state of mind.

These signs of a lost world—the world of the Heidelbergs and Neanderthals—are still to be found even with just about anywhere in our culture: art, customs, laws, language, perception, architecture, science, beliefs and even religions. It sounds perhaps an overstatement to link Neanderthals with our religiosity. Still, our need for spirituality means a yearning for liberation from the burden of humanity. Freedom can be found before the modern human emergence, about 100.000 years ago. The cultures are partly products of the human biological memory, reflecting the same distant past. All the critical mysteries of our culture are to deal with this phenomenon in one way or another. We know that only creative and imaginative people spark our culture. These people can express real adulthood in beliefs, rituals, art, work, and other products. These people’s experiences unite us to the distant past and the wild nature, and therefore they persist—in various forms, though—from era to era. The similarity of experiences also allows us to assess the different manifestations of culture on a comparable basis. At first sight, the cultures seem not as products of ”the negative mind”, but the cultures always carry ambiguity and interpretation, issues arising from the fact that we cannot describe most profound experiences unambiguously nor exhaustively through reason.

Reflections on Gilgamesh

The world’s oldest—and one of the most interesting—preserved epic, the epic of Gilgamesh, can be interpreted as reflecting the emergence of civilisations against the weakening archaic adulthood. It is quite likely that similar but lost descriptions, have been in oral tradition for thousands earlier. In the Gilgamesh epic, the archaic human Enkidu, a mythical male figure, is often considered a Neanderthal man.

The goddess Aruru, she washed her hands,

took a pinch of clay, threw it down in the wild.

In the wild she created Enkidu, the hero,

offspring of silence, knit strong by Ninurta.

All his body is matted with hair,

he bears long tresses like those of a woman:

the hair of his head grows thickly as barley,

he knows not a people, nor even a country.

Coated in hair like the God of animals,

with the gazelles he grazes on grasses,

joining the throng with the game at the water-hole,

his heart delighting with the beasts in the water.

Enkidu with bull’s ears.

We should notice that here the myth encounters our actual archaeological past. Enkidu is called an ”offspring of silence”, essentially an accurate description of the adult Neanderthals and Heidelbergs, who did not have a language! Enkidu also could not recognise people or countries because he could not distinguish between things humanely. King Gilgamesh commanded this odd creature to be tamed and weaned from the animals with the charm of Shamhat, the temple prostitute. What could be the reasoning behind such an idea? A perfect one because this reminds the story of the Fall of man in the Bible. Once again, sexuality is a sign of civilisation since only discovering sexuality makes the virgin wild man, Enkidu, suitable for human society. The epic does not try to argue that sexuality alone would create civilisations. Still, it presents sexuality as a symptom of modern humans (or adolescence) and, thus, a distinguishing factor between modern humans and animals (Neanderthal man and homo heidelbergensis included). After the ”re-education” period, Gilgamesh describes how domesticated Enkidu becomes a modern human:

Enkidu had defiled his body so pure,

his legs stood still, though his herd was in motion.

Enkidu was weakened, could not run as before,

but now he had reason, and wide understanding.

So Enkidu learned to understand speech and the fact that he needed a companion. He also forgot his homeland. He learned to eat bread and drink beer, and wash. Gilgamesh, the hero-king of Uruk, tamed this wild and savage man, ”born in the uplands”, as a partner for himself.

This delicate tale reveals a significant connection between inexplicable divinity and savagery, whilst the story soon states the exact relationship as inappropriate for civilisation. The message is that only when Enkidu fouled his virginity and became weaker, i.e. human-like, the society (in the form of Shamhat, the temple prostitute) see him as god-like:

You are handsome, Enkidu, you are just like a god!

Why with the beasts do you wander the wild?

Come, I will take you Uruk-the-Sheepfold,

to the sacred temple, home of Anu and Ishtar

Unfortunately, we cannot find this insight in the literature later. The story reflects a changeover from adulthood toward adolescence, typical for the civilisationse truly remarkable thing here is that the role of the modern human (Shamhat) is to act as a mediator. It is important to note that in myths, the part of gods seems to be to educate or modernise the archaic human despite losing his ability to live in and act with nature. In Gilgamesh, the first encounter with the uncivilised archaic human, i.e. Enkidu, caused a shock in a hunter who saw him:

When the hunter saw him, his expression froze,

but he with his herds — he went back to his lair.

[The hunter was] troubled, subdued and silent,

his mood [was despondent,] his features gloomy.

In his heart there was sorrow,

his face resembled [one come from] afar.

The experience could be the same as some modern humans’ when facing the Neanderthals 35,000 years ago. But, this was also how modern humans felt the Neanderthals: it was far from what they could understand and accept about themselves.

The gods in these myths are the companions of men just because they were born in civilisations and not in the wild, although they are initially from the wild. The essence of cultures and urban societies described in the Gilgamesh epic is that divinity originated in nature, but it had to be tamed and tidied up for civilisations. The Gilgamesh epic tells us that adulthood, i.e., the original and raw divinity, is highly invalid as a building material for the urban culture since the adolescent human fears the irrational and intuitive from the bottom of his heart. So urban cultures tidied up and rejuvenated God. Religions, representing the official spirituality of the civilisation, disguise and clean up all scary and licentious elements at an early age from their Gods. Civilisation means bringing the original divine characteristics, namely speechlessness, the lack of sociality and volition, and absurdity to human cultures in their opposed forms: speechlessness as language, lack of sociality as love, lack of will as sexuality, and absurdity as morality. The big problems of all Western civilisations emerge from this incredible and blatant incongruousness.