Mysticism and Philosophy is a book on mystical experience published by Walter Terence Stace in 1960. Stace’s work is, as its name implies, a philosophical work. It is not about life skills or an ethical guide but a clarification of concepts (mostly mystical experience vs psychedelic experience) and shows the historical roots of Western mysticism. The work attempts to place mystical experiences on the map of philosophy and processes them with the tools provided by philosophy. The work is, in my view, the most advanced reflection on the philosophical aspects of the mystical experience in terms of Western thought.

Let us clarify one thing: mystical experience is not a trivial matter, not just another thing to explain, and indeed not an easy question. W. T. Stace is one of those philosophers who looked beyond his research objects and tried to understand them by comparing and combining the views of different thinkers. His goal is, if not a scientific consensus, at least some harmony of everyday life and coherence of facts. He does not hesitate to dispute the prevailing views, whether from mysticism or philosophy if they do not seem reasonable. He is not a reductionist and thus does not seek to explain a mystical or religious experience as insignificant. Accordingly, as a philosopher, he has not, in principle, set out to define mystical and religious experiences as mere fantasies. He is Immanuel Kant’s heir because he doesn’t think theoretical knowledge alone could explain the world. The contradiction, one of the work’s critical elements, remains unresolved in his reading. It shows the existence of two different worlds, “temporal” and “eternal”.

Walter Terence Stace (1886–1967)

Stace brought up exciting aspects of mysticism. One of them was the question of whether animals can have mystical experiences. While this seems somewhat irrelevant and unproven, it contains some solid implicit claims. On the other hand, mysticism seems dubious to the church’s doctrines, so it is no wonder that mystics have been repeatedly overborne and subjected to threats by the theologians and the ecclesiastical authorities of the church.

What is a mystical experience?

At least reading the mystical literature makes this question difficult to answer. The mystical experience is well worth its name: it is mystical in many ways. But unfortunately, there is no consensus on what it is, why it is, how it works, why it appears, why it disappears and why only a few people experience it. It is a mystery to all who have not experienced it and those who have. As a result, there are countless different and partly contradictory interpretations.

Its interpretive nature has also been part of the reason for the underestimation. It has been easy to think of it as mere imagination, and people experience it as hypersensitive and whimsical. Yet, mystical experience has a solid cultural position, despite its marginalisation and strong anomaly, and it is reflected above all in religions and the arts. It played a more vital role in folk cultures through beliefs and customs. Still, in cultures dominated by civilisation, its importance has diminished—mainly because mysticism does not adapt to be shared, for example, in writing. Another reason is the illogicality of mysticism. Thus, mysticism is more challenging to discuss in civilisations and urban cultures than indigenous and folk cultures.

Experience with many names

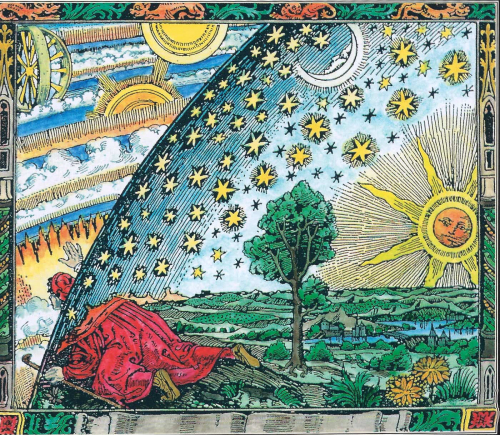

This strange experience has most often been called a mystical experience. While Stace doesn’t study the terminology of “mysticism” itself, it’s good to know something about it. Sometimes the word mystical is allegedly related to biblical, liturgical, spiritual, and early and medieval Christianity. However, the meaning of the term mysticism is older. Behind the words “mystery”, “myth”, and “mysticism” is the Greek word musteion, meaning “to close” or “to conceal”, which refers to a” secret rite” of the ancient Greek city of Eleusis. The word mustikós (μυστικός) means” connected with the mysteries” or “private, secret” (as in Modern Greek). In other words, Eleusis is terminologically the mother of all mysteries.

The city of Eleusis resides on a fertile plain outside Athens. Twice a year, a ritual was organised in which all Greeks, both men and women, could participate. Numerous scholars have proposed that the power of the Eleusinian mysteries came from the kykeon (ancient Greek drink) functioning as an entheogen or psychedelic agent in the ritual. It is known that participants were not allowed to reveal what happened there in the ceremony. “Mystery” signifies this secrecy: participants were bound by a vow of silence given to the gods. The Eleusinian Mysteries is a white page in history, although the mystery tradition continued for over a thousand years.

However, the mystical experience also has many other names. Stace referred to the phrase “unitary consciousness”. The term “pure conscious event” is also used in the study. “Altered states of consciousness”, or ASC, is a term used in this context, but it also covers, e.g. hypnotic states. “Oceanic consciousness/sentiment” comes from Romain Rolland (1866–1944) [Source], numinous from Rudolf Otto (1869–1937), and cosmic conscience from Richard Bucke (1837–1902). Also, the terms transpersonal and transcendental experience are used.

The terms” religious experience”, “spiritual experience”, and “sacred experience” are often synonymous with mystical experience. They have similar features. According to William James (1842-1910), the mystical experience was at the heart of religions. Religions were based on “the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand to whatever they may consider divine”. The term nondualism also refers to the experience. It refers to a mature state of consciousness in which the dichotomy of I–other is” transcended”, and awareness is described as” centerless” and” without dichotomies”. [More]

A personal experience

I’m happy to share one more mystical experience here, and that’s mine, of course. It dates back to March 5th 1982. I wrote down the feelings it evoked immediately, and now I find it easy to explore similar experiences of others. I later collected my notes and came up with two lists based on them.

The first is the list of my subjective sentiment about the experience (note: I’m not trying to fit these into the Stace lists that you will find further below):

Common Characteristics of Extrovertive Mystical Experiences by Stace

- The Unifying Vision—all things are One

- The more concrete apprehension of the One as an inner subjectivity, or Life, in all things

- Sense of objectivity or reality

- Blessedness, peace, etc.

- A feeling of the holy, sacred, or divine

- Paradoxicality

Alleged by mystics to be ineffable

Common Characteristics of Introvertive Mystical Experiences by Stace

- The Unitary Consciousness; the One, the Void; pure consciousness

- Nonspatial, nontemporal

- Sense of objectivity or reality

- Blessedness, peace, etc.

- Feeling of the holy, sacred, or divine

- Paradoxicality

- Alleged by mystics to be ineffable

In relation to this comparison, W. T. Stace states the following:

“These facts seem to suggest that the extrovertive experience, although we recognise it as a distinct type, is actually on a lower level than the introvertive type; that is to say, it is an incomplete kind of experience which finds its completion and fulfilment in the introvertive kind of experience. The extrovertive kind shows a partly realised tendency to unity which the introvertive kind completely realises. In the introvertive type, the multiplicity has been wholly obliterated and therefore must be spaceless and timeless since space and time are themselves principles of multiplicity. But in the extrovertive experience, the multiplicity seems to be, as it were, only half absorbed in the unity. The multiple items are still there, the “blades of grass, wood, and stone” mentioned by Eckhart, but yet are nevertheless “all one.” That is the paradox. But in the same sense as the multiple items are still recognisably “there,” so also must be at least the spatial relations between the items and possibly in some cases the time relations too.”

Mysticism versus philosophy

Mysticism and philosophy is an exciting work by its very subject. The juxtaposition of mysticism and philosophy is not intended to produce a philosophy of mysticism but rather a fierce and equal duel between mysticism and philosophy. Philosophy does not take precedence over mysticism to preach the proper use of language. Here, mysticism challenges philosophy and impels philosophy to swallow a taste of its own medicine. Both philosophy and mysticism are trying their best, but one wonders if it is possible to reach an agreement. Mysticism tries to lure philosophy out of its playpen, where it has been shouting for advice for two millennia, to show whether its teachings are also valid in the real world. After all, the problem is clearly that these disciplines do not live in the same reality.

Mysticism is a tremendous challenge to philosophy. The point is to force mysticism to disagree with the philosophy. Challenging philosophy does not mean any minor disagreement with mysticism. It represents an argument for the complete inability of philosophy to answer major human questions. All that’s left of philosophy is research methods. Mysticism rightly argues that philosophy is of no help to those who ponder the mystic experience. Philosophy marinates in its broths to no longer taste good. Stace tries to find a reconciliation between the extremes. He is not unequivocally and clearly on either side.

Stace himself feels his role is to bring this fighting couple to the same table and resolve their disputes. Those who have criticised Stace’s analysis do not understand this approach but attack him as a philosopher of mysticism, which I do not think he is. Of course, he could be that because he gets his tools from philosophy, but he is more of a referee. His only chance is to decide what to think if an agreement is still impossible. A compromise could arise if one finds a way in which mysticism would be more philosophical or if philosophy admits to being more mystical.

Stace does not seek to explain the mystical experience itself but distinguishes it from other experiences. That may be the best philosophy can offer. Unfortunately, however, the limits of philosophy are the limits of language, and because mystical experience is beyond practically everything linguistic, philosophy cannot extend to the domain of mystical experience.

While I find the work necessary, Stace is mistaken on some points. First, it is questionable to consider introvert mysticism more essential than extrovert mysticism. I believe Stace believes his way to be justified because there are far more people with introverted experiences than extroverted ones. I see no justification for this. Here, therefore, the external proof is decisive. Second, Stace’s method looks for common and distinguishing features and compares combinations of different parts. He most often uses mere logic to compare interpretations with each other. He never really asks if a mystical experience can have any earthly explanation, what it is, or what it is all about. Still, he takes the religious and cultural framework for granted and only considers what interpretations he could think of as the most plausible philosophically. Here, of course, he is at his weakest, as he grounds his research on conjectures rather than tested, that is, personal knowledge. But he lacks that.

Stace may not want to set boundaries for philosophy, but he will do so involuntarily. His purpose is to study the phenomenon objectively and with a philosophical attitude. Setting the conditions for interpretation is perhaps more important than the study’s results. For example, Stace agrees with the philosophy that abstract thinking is only a part—and relatively limited—of a person’s spiritual life. Thus Stace will have shown the weakness of philosophy. But, of course, all philosophical studies do the same; they show the failings of philosophy even though they aren’t interpreted as weaknesses. Weaknesses are only said to be problematic.

The work shows, in particular, the limits of analytical philosophy.

The danger of philosophy lies here because it nullifies all further research if the questions are answered thoroughly enough. That seems to have happened to Stace. He manages to say that philosophy is of no more use than what he has written. He does a good job, but only to reveal the limits of his discipline. It is difficult to say whether he was aware of that.

I agree with Stace that mystical experience is the key to correctly understanding human consciousness. The fact that mysticism is still mysticism coincidentally describes that man is still a mystery to himself. That can be insignificant parallelism and pure coincidence, but it can also be the seed of truth. Just as mysticism has the reputation of an anarchist within religions, science has its anarchists, whose views not everyone agrees to accept. The connection between mysticism and science is hardly mentioned, as the fields seem opposites. There is a competitive situation. If there is one, the subject of the study must be shared; only the means differ.